The following article presents my understanding of the concepts discussed by Dave Farley regarding Acceptance Testing, aiming to address questions such as:

How do we fail fast?

How do we make our testing scalable?

Are we ready to release?

Please follow him on his Continuous Delivery YouTube channel. Now, let's begin.

What is an Acceptance Test?

It is a test that asserts that the code does what the user wants, providing timely feedback.

Who owns the Acceptance Test?

The faster we receive feedback from acceptance tests, the faster we can react. In addition, developers are constantly changing the code and possibly breaking the tests. Therefore, developers should have the responsibility to keep them working.

What are the characteristics of a good Acceptance Test?

Separate WHAT from HOW

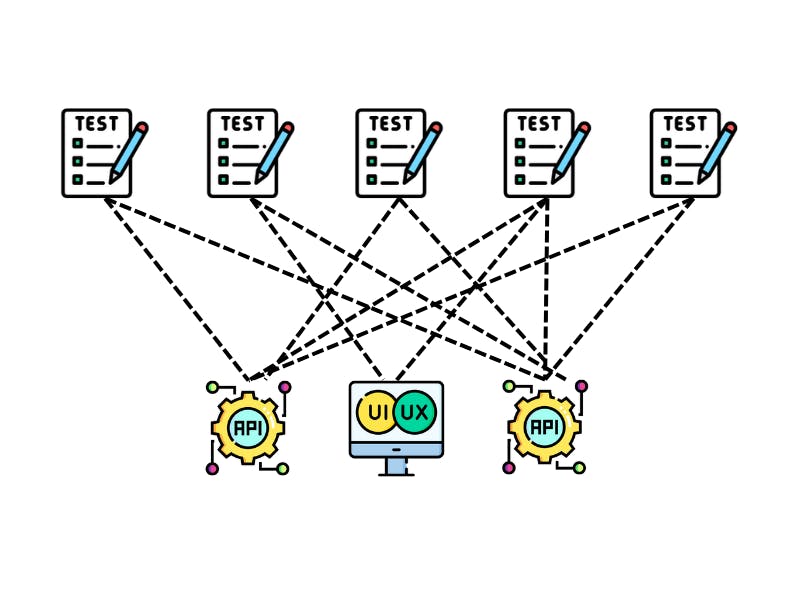

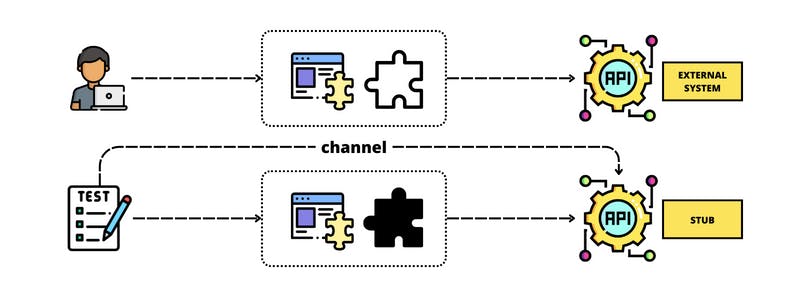

Acceptance tests often are tightly coupled with the system under test (SUT), which may result in low-quality, expensive, unreliable, and error-prone tests.

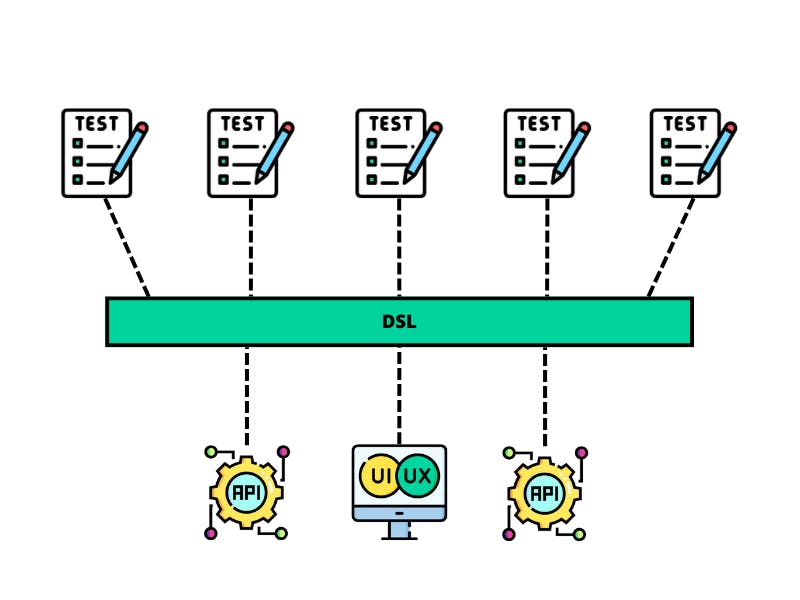

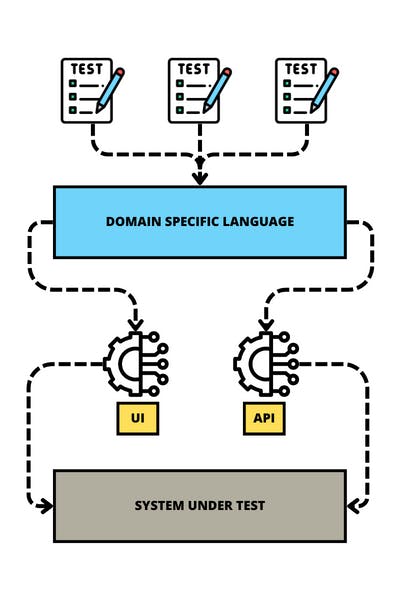

In the image above, what happens if we decide to replace an API with a UI or an API change? Surely, we would have to rewrite several tests. Our tests should say nothing about HOW the system works. We should have a clear separation between WHAT the system does from HOW it does. The tests should be focused on WHAT the user wants of the system, and an effective way to express it is by using the language of the problem domain, a Domain Specific Language (DSL).

A DSL can be introduced as an additional layer of abstraction. That describes the tests from the business point of view saying nothing about how to interact with the SUT. An effective DSL should be written in the language of the domain problem, be simple to read and use, and be shareable across multiple tests.

Isolation

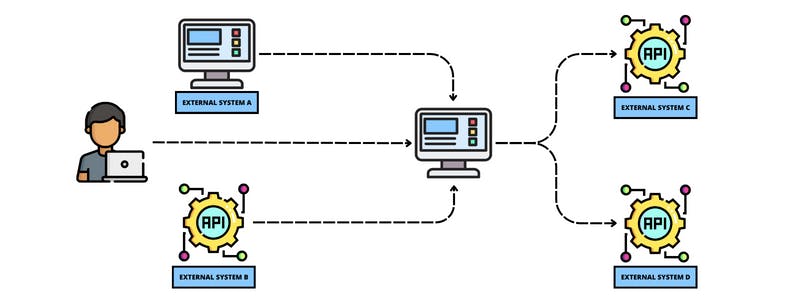

Isolation can be viewed from various perspectives, and it's vital in our testing strategy. Let's begin with the isolation of the SUT. We should ask ourselves a question: What are the boundaries of our system?

Typically, a system interacts with others (downstream and upstream). During the testing, a common strategy could be to apply an End-to-End approach. However, there is an issue; in most cases, these external systems are beyond our control. That limits how we can test our system, resulting in less precise tests.

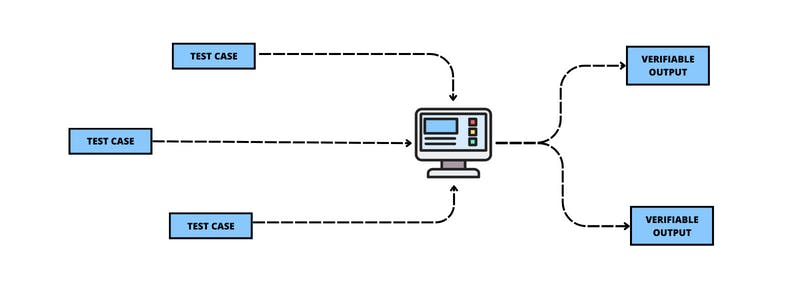

So, what if we replace each external interaction with either a test case or a verifiable output? We can write test cases at the boundaries of our system that communicate with it through its default interface. With that in place, we can now simulate every unusual scenario that might not be generated by the external systems. However, there is a downside to this approach: the interfaces between systems can break, and our tests would never detect it. Hopefully, there is another testing strategy to solve this problem, Contract Testing.

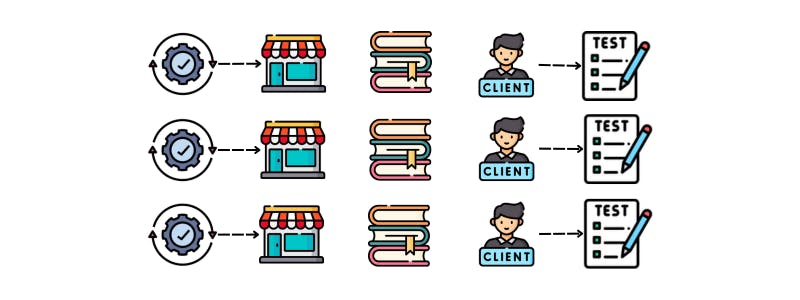

The second type of isolation is test case isolation. Each test should set up everything required to run, with the assumption that multiple instances could be executed in parallel. Therefore, we must avoid any dependency between tests, particularly those related to data.

For instance, in a book retail system, we must ensure that a new store, book, and client are created each time the test case is executed. We must be capable of placing the system in the state we want to be.

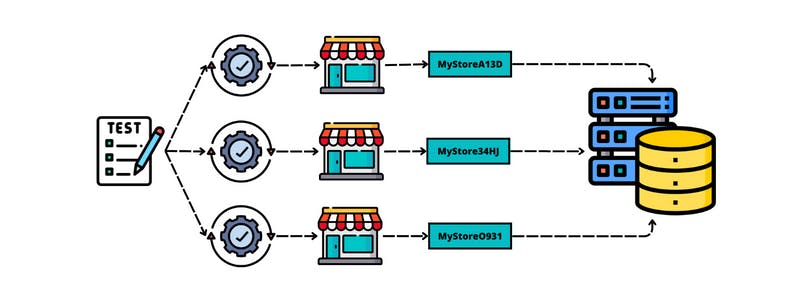

Finally, the last type of isolation is temporal isolation. Our tests must be repeatable, if we run our test case twice it should work both times.

For instance, let's imagine that our test requires the creation of a store named MyStore. To avoid possible conflicts, we could modify the name by adding a few unique characters.

Repeatable

Closely related to the SUT isolation, there are instances where we need to obtain data from other systems to complete our processes.

To achieve a deterministic test, we must maintain control over all variables that could potentially impact the test. Thus, the only way to achieve this is by faking the dependency, to only focus our efforts on our SUT.

Four Layers Architecture for Testing

Lines above, we discussed the essential features required for a clear separation of concerns. Without this separation, high-level functional tests become fragile when the system under test changes.

The structure consists of four layers:

Test Cases: Test Cases are written using the DSL instead of technical interactions with the SUT. In this manner, these executable specifications maintain a very loose coupling with the SUT.

DSL: The second layer implements the DSL, which is a problem-specific language shared by many test cases.

Adapters/Drivers: These adapters translate the DSL into actual interaction with the last layer, the SUT.

In conclusion, Acceptance Testing is a crucial aspect of software development that ensures the system meets user requirements. By embracing key principles such as isolating the system under test, creating test case and temporal isolation, and using a Domain Specific Language, we can develop high-quality and maintainable tests. Implementing a four-layer architecture further enhances the separation of concerns, making our tests more robust and efficient. Ultimately, this leads to a faster, more scalable testing process that helps us confidently answer whether our software is ready for release. Thanks, and happy coding.